Global uranium market faces shortage on surging Indian NPP expansion demand

A projected tenfold increase in India’s nuclear power capacity by 2047 is poised to upend the uranium market, creating a long-term supply-demand imbalance that analysts say the current production system is ill-equipped to manage.

India has set a target to boost its nuclear generation capacity from the current 7.5 gigawatts to 100 gigawatts by 2047, according to the Department of Atomic Energy. Meeting that goal would add approximately 23mn kilos of annual uranium demand—equivalent to around 30% of global uranium production today, based on World Nuclear Association data.

“This creates a projected cumulative deficit of 770,000kg … nearly 10 times current annual uranium production,” industry analyst Lukas Ekwueme said. “The uranium supply–demand model is broken.”

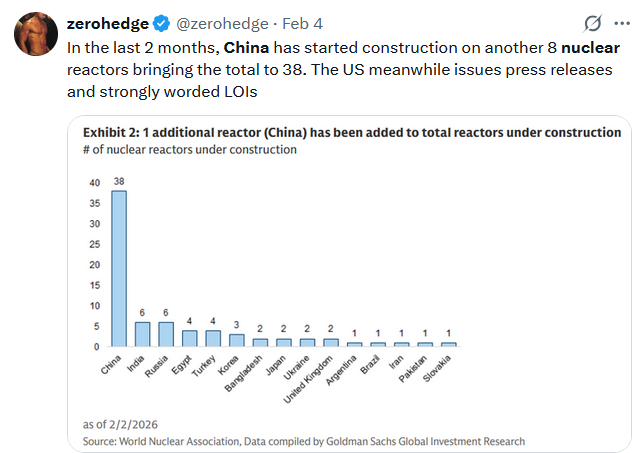

The forecast shortfall reflects a confluence of rising demand and constrained supply. India is not alone in turning to nuclear power to meet decarbonisation goals. China has emerged as the world's leading builder of nuclear power plants, completing new reactors in as little as five years and currently has around 38 nuclear power plants (NPPs) under construction.

Russia is also massively expanding its NPP fleet and nuclear exports are booming with three dozen international projects on the state-owned Rosatom’s docket. Several European nations are also planning to expand or extend their nuclear fleets. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global nuclear capacity to increase by more than 40% by 2050 under its stated policy scenario.

However, global uranium supply is under pressure. While several countries mine uranium, including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Canada and Niger, enriching the ore remains dominated by Russia.

But several major global mines remain shuttered following a prolonged bear market after the Fukushima disaster in 2011. While prices have rebounded sharply—spot uranium surpassed $220 per kilogram ($100 per pound) in January for the first time since 2007—project development has lagged.

Kazakhstan, the world’s largest uranium producer, has faced production challenges due to wellfield constraints and limited access to sulphuric acid, a key input. Canada’s Cameco has also cited labour shortages and technical difficulties at its flagship operations.

“There is no quick fix,” said Ekwueme. “It takes years to bring a uranium mine online, and few producers have the balance sheets or regulatory certainty to make the leap today.”

India’s ambitious nuclear programme is part of a broader push to reduce dependence on coal and imported fossil fuels. With more than 70% of its electricity still generated from coal, Delhi aims to decarbonise while supporting its rapidly growing population and industrial base.

Yet India currently imports all its uranium, relying primarily on suppliers in Kazakhstan, Canada, and Uzbekistan. Supply security could emerge as a strategic concern in the coming decades, particularly as Western utilities compete for the same barrels in an increasingly tight market.

The biggest uranium producer Kazakhstan is seeing a production peak. It produces about 40% of the global uranium supply, but by 2046, production from existing mines will decline by 80%, say analysts. Given it usually takes about 20 years from exploration to first production, there is likely to be a supply short fall unless billions are spent on exploration just to offset Kazakhstan’s decline curve.

However, President Vladimir Putin claims Russia has a solution. He announced in September Russia has made a nuclear technology breakthrough and has developed a closed fuel cycle power system to tackle global uranium shortages. Russia is moving ahead with the development of its first industrial-scale closed fuel cycle reactor, the BREST-OD-300, which would be a gamechanger if the claims are confirmed.

A closed fuel cycle reactor is a fuel management strategy, not a specific reactor type. Spent nuclear fuel is reprocessed and reused, rather than being treated as waste after one use, as in an open fuel cycle. The BREST-OD-300 recycles fuel on-site, enabling continuous reuse of uranium and plutonium. The reactor is similar to a fast breeder reactor that uses fast neutrons, unlike conventional reactors, and is specifically designed to "breed" more fissile material than it consumes.

China also claims that it has cracked the problem of fusion reactors which would also solve the fuel problem. The Shanghai-based commercial fusion energy company Energy Singularity announced on June 19 that it has successfully built the world’s first fusion reactor that puts out more energy than it takes in to run it, The Global Times reported.

Follow us online