Latin American oil leaders will not be dislodged by Venezuelan comeback, says Rystad

Brazil, Argentina and Guyana will continue to lead investment.

WHAT: Latin American oil giants will shrug off Venezuelan inroads.

WHY: Venezuela will struggle to attract major investment, and its infrastructure is dilapidated.

WHAT NEXT: Brazil Argentina and Guyana will likely deliver over 700,000 bpd of new output in 2026.

Latin America’s oil landscape is entering a pivotal phase, with Argentina, Guyana and Brazil set to drive most of the region’s production gains in 2026 even as Venezuela edges back into international markets.

The potential reappearance of Venezuelan crude is stirring debate about capital allocation, but Rystad Energy analysts indicate that the dominant trio will continue to shape supply growth for years to come.

A recent assessment from indicates that major developments in Argentina, Guyana and Brazil are on track to deliver more than 700,000 barrels per day (bpd) of additional output this year alone.

That expansion is expected to keep them ahead of Venezuela through the end of the decade. Although as much as 300,000 bpd of Venezuelan crude could return in the near term, the consultancy suggests that a broad shift of capital away from established growth centres toward Venezuela’s strained infrastructure remains improbable given ongoing business risks.

“A Venezuelan oil industry makeover will be costly and lengthy, with the big three in the region – Argentina, Guyana and Brazil – remaining largely indifferent to the estimated, near-term return of Venezuelan crude,” said Radhika Bansal, Rystad’s vice president for oil & gas research.

She added that market dynamics, rather than geopolitics alone, are shaping boardroom decisions. “Oversupply, whether from Venezuelan or even Iranian barrels, is what is truly testing the financial resilience of operators who would otherwise gain from a revived oil industry in the Bolivarian Republic,” she said.

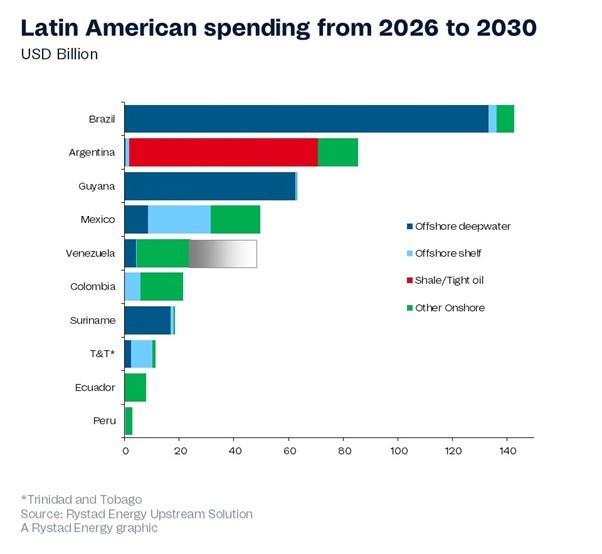

Regional investment

Regional investment is forecast to rise in 2026, but the amount of conventional reserves being sanctioned is projected to fall sharply compared with last year—down about 45%.

That contraction reflects a more cautious stance, with companies concentrating on ventures that promise dependable returns. Final investment decisions across Latin America were subdued last year and are likely to remain restrained.

Capital spending patterns underscore this selectivity. Offshore frontier projects in Guyana and Suriname are poised to attract substantial greenfield funding, while Argentina is leading reinvestment in existing assets as Vaca Muerta accelerates.

Brazil remains the cornerstone of regional expansion, with production anticipated to exceed 4.2mn bpd in 2026. New floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels are central to that increase, reinforcing the scale and cost efficiency of its pre-salt portfolio.

Overall crude supply from Latin America is expected to surpass 8.8mn bpd this year, accounting for a significant portion of non-OPEC+ growth. Yet the region is no longer moving in unison. Instead, the “big three” are widening the gap with neighbours that struggle to keep pace.

Argentina’s shale industry is a critical engine behind the investment upswing. Spending in the country’s unconventional sector is projected to climb from $9.4bn in 2025 to nearly $11bn in 2026.

Deepwater activity across the region is also gaining momentum, with anticipated investment of $42bn, marking a 7.7% annual increase.

Strong economics at the Vaca Muerta shale region, steady output from Brazil’s pre-salt fields and continued discoveries offshore Guyana and Suriname underpin that trajectory.

Venezuela is complex

Against this backdrop, Venezuela presents a more complex picture. Large international oil companies remain wary of long-term exposure due to lingering legal ambiguities and fragile institutional frameworks.

Even so, traders and smaller operators are exploring structured, shorter-term arrangements.

Access to Venezuela through specific licenses can reduce initial capital requirements, while US Gulf Coast refiners value Venezuela’s heavy crude as discounted feedstock. Trading houses with expertise in blending and logistics are positioned to manage regulatory constraints tied to these barrels.

Recent policy shifts in Washington have also altered the landscape. The US authorised traders Trafigura and Vitol to market unsanctioned Venezuelan oil following the January 3 capture of former president Nicolás Maduro.

Subsequently, sanctions on oil exports were eased with restrictions, enabling state-owned PDVSA to sell cargoes directly to approved buyers abroad. These measures have increased the availability of Venezuelan crude without fundamentally reshaping Brazil’s trade flows.

Executives speaking at the Argus Americas Crude Summit in Houston have emphasised that rising Venezuelan heavy sour supplies are unlikely to crowd out Brazilian grades in global markets. The two streams cater to different refineries and pricing structures. In the near term, shipments from Venezuela to the US are expected to stay below 300,000 bpd, while Brazil continues directing most exports toward Asia.

Industry participants noted that Venezuelan crude characteristics make it well-suited for US refiners, where it competes with other heavy sour streams such as Western Canadian Select and barrels from Mexico, Ecuador and Colombia.

In contrast, Brazil’s lighter and medium grades have established a firm foothold in Asian markets. Brazil, currently the world’s sixth-largest oil producer, is adding roughly 400,000 bpd in 2025 as part of the broader regional upswing, and those incremental volumes are projected to flow predominantly eastward through the decade.

Growing output in Brazil and Argentina may also spur additional co-loaded shipments to China. Petrobras has already transported blended Brazilian and Argentine cargoes on very large crude carriers, and Argentina is expanding infrastructure to boost exports of its Medanito grade to Asian buyers.

Venezuela’s neighbours

For neighbouring countries, Venezuela’s re-entry presents mixed implications. Trinidad and Tobago could benefit from cross-border offshore gas supplies to feed its liquefied natural gas facilities.

Colombia, however, may encounter stiffer competition for investment capital given its limited inventory of new oil prospects. A revitalised Venezuelan industry could also draw on specialized labour currently employed across the border.

Despite these shifting currents, long-cycle offshore projects in Brazil, Guyana and Suriname retain economic appeal across a range of oil price scenarios. Their competitive breakeven levels and established development plans make them less vulnerable to short-term fluctuations tied to Venezuelan supply.

Even Argentina’s shale play, though more flexible in timing, is committed to infrastructure expansion that supports resilience in a softer price environment.

Rystad’s Bansal suggested that the long-term significance of Venezuelan barrels hinges on demand trends and disciplined investment choices.

“Supposing oil demand stays resilient through 2035, and the impact of years-long underinvestment is fully felt, Venezuelan barrels would become far more relevant,” she said.

“If the industry starts making more long term, economically rational choices now, Venezuelan oil production could make sense in a higher oil price environment. However, more attractive barrels will still be at play, with Venezuela’s extra-heavy, emissions-intensive oil posing persistent challenges,” she said.

For now, the centre of gravity in Latin American oil remains firmly anchored in Buenos Aires, Georgetown and Rio de Janeiro. Venezuela’s gradual return may alter trade patterns at the margins, but the region’s growth story in 2026 continues to be written by the three producers with scale, capital discipline and competitive costs on their side.

Follow us online