LONG READ: How oil price discounts became a barometer of the sanction’s effectiveness

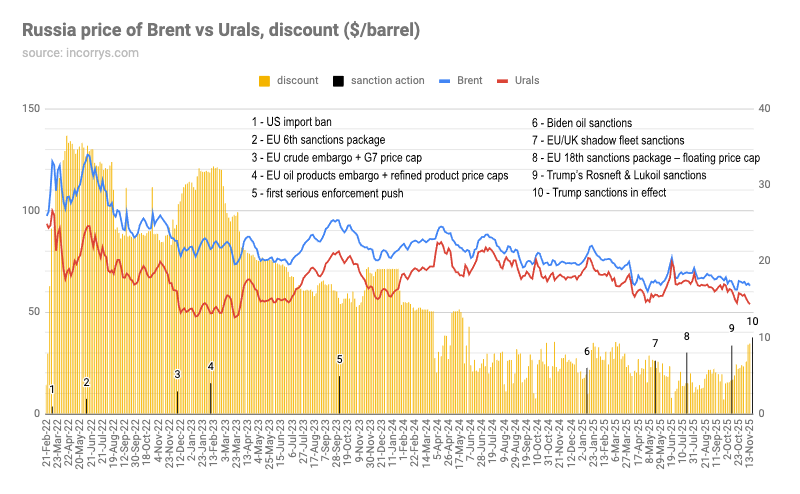

When Russian troops crossed into Ukraine in February 2022, the country’s main crude export blend, Urals, was still trading in line with its traditional discount to North Sea Brent. On the day before the war on February 21 2022, a barrel of Brent cost $97.26 and Urals was $93.44, a modest discount of $3.82, according to data from Incorrys.

Tensions in January were already high and the US had been warning that Russia could invade Ukraine “any day” since the November before. In calmer times the cost of Urals is usually around $2 less than Brent, but after the war started that discount blew out to a massive $30, cutting deeply into the Kremlin’s revenues.

The West has focused on sanctioning Russia’s oil exports in the hope of bleeding the Kremlin of enough money that Russian President Vladimir Putin will be forced to the negotiating table. Just how wide the discount between the cost of Urals to a barrel of Brent has become, is an excellent barometer of how successful those sanctions are.

Russia is budgeted to spend an estimated $160bn on the military this year, the most ever. That is set against the $166bn it earnt from oil exports in 2022, $99bn (2023), $192bn (2024) and is on course to earn $200bn this year, just from oil and gas exports.

Panic stations 2022

Within days of the invasion, that relationship was blown apart. By February 25, the Urals discount had already blown out to $7.95. On March 3 it reached $16.71, and by March 8, when Washington announced the “US import ban” (1 on the chart) on Russian oil, Brent had surged to $124.07 while Urals lagged at $99.80 – a massive gap of $24.27 per barrel.

The West was hitting Russia with the most extreme sanctions regime ever imposed on a country. A raft of crushing measures were introduced in only a matter of weeks, the two most extreme being the freezing of $300bn of Central Bank of Russia (CBR) reserves and a ban on using the SWIFT messaging service that effectively cut Russia off from the dollar.

Oil traders panicked and throughout the spring of 2022 the market “self-sanctioned” Russian exports. They wouldn’t touch the Urals blend oil with a barge pole. Storage facilities in Russia started to fill to overflowing, and tankers carrying Urals were aimlessly wandering about at sea to find a buyer. It went on for months.

But then the deals started happening. Oil traders are a venal bunch . Offer them a barrel of oil at two thirds the market rate and someone is going to buy it. After all, as soon as crude is refined it ceases to be “Russian” anymore.

All this was happening well before any formal sanctions were placed on Russian oil. By August Urals was starting to find buyers in Asia, but still at a punishing discount: from March 18 to May 27 2022 the discount oscillated around $29–36 per barrel.

The EU’s sixth sanctions package (2), agreed in early June 2022, formalised what markets had already anticipated: a phased ban on seaborne imports of Russian crude and oil products, plus restrictions on shipping and insurance. On June 6 that year, Brent stood at $124.25 and Urals at $90.45, a discount of $33.80. The gap remained in the low-to-mid 30s through June and much of July. Only from mid-August did it start to narrow meaningfully, slipping below $30 by August 19 for the first time since the war started and into the mid-20s by late August. The market was getting used to the new realities and a new distribution system was emerging, where the unscrupulous could make a very fat margin on oil trades.

From the autumn of 2022, the discount stabilised in the low-to-mid $20s, even as Brent itself began to drift lower. Between September 5 and November 30, the data shows the Urals discount mostly between $22 and $24 per barrel, with temporary spikes such as $29.60 on September 15 and $25.49 on November 29. Markets were waiting for the next big event, widely discussed at the time: the EU embargo and G7 oil price cap sanctions as part of twin sanctions on crude and oil products.

EU twin oil sanctions 2023

The first trigger was pulled on December 5, when the EU crude embargo and G7 price cap (3) entered into force, effectively banning the import of Russian crude to Europe. On that day Brent traded at $85.00, Urals at $60.24, widening the discount to $24.76, before blowing out again in the following days to go back to a $30 discount again. By the time Christmas came, the discount had reached $30.50.

Things got even tougher for Russia when the second part of the EU sanction on oil products embargo and refined product price caps (4) came into effect on February 5 in early 2023 and pushed the spread even wider. The data shows a discount of $31.58 on the implementation date, (Brent $80.99, Urals $49.41).

Through February the discount hovered just above $32, peaking at $32.40 on February 13. For Russia’s budget, this was a double whammy: world oil prices had come off their 2022 highs, and Urals was trading at more than $30 below Brent. Brussels was euphoric. The sanctions appeared to be working and the Russian economy was reeling.

But the buzz of success began to wear off as the market once again did its thing. The EU’s twin sanctions ended tanker deliveries to Europe. It takes about a week to sail from Russia’s Baltic ports to somewhere like Rotterdam, but two months to get to Asia. In the first months of 2023 Russia scrambled to redirect its entire oil exports from Europe to Asia. As the first tankers arrived home from trips to India and China four months later to pick up their second load, the conveyor belt was established. Although the trip is longer and more expensive, if you have enough ships – and the Kremlin started investing heavily into building up its shadow fleet in those four months – once the circle is closed the rate of the exports returns to normal, some 5mbpd.

This transition is very clear in the discount data which had fallen heavily from over $30 to under $20 by May – four months after the EU sanctions – but it also shows up in the federal budget receipts from that year. (chart) The government ran a huge RUB1.6 trillion deficit in January 2023, but that returned to a profit in May the same year and incomes were more or less back to normal in the second half of the year.

Ukraine’s supporters tracking the effect of sanctions like the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) began calling for better enforcement of the sanctions and the antics of the shadow fleet were widely reported. This pressure built as it became increasingly obvious that the sanctions were not having the crushing effect on the Russian economy hoped for.

India and China absorbed more barrels. The shadow fleet continued to grow. Traders learned how to work within – or around – the price cap system and even EU-regulated Greek tankers were taking advantage of the big margins on offer; Greek tankers legally make up about a fifth of the shadow fleet, by keeping the contracted cost of a barrel of oil on their ships below the threshold $60 limit.

The Urals discount steadily compressed in the summer of 2023. By April 3 2023 it was $21.84; by June 1, $19.94. As the summer wore on, the gap fell into the high teens, settling in a $16–20 range between July and December.

By the autumn, Western politicians decided that something must be done and on October 2 launched the “first serious enforcement push” (5) against price-cap evasion and the shadow fleet. On that date, the Brent–Urals spread was $15.20, slightly tighter than in September but half what it was at the start of the war. Enforcement did not immediately blow the discount back out, but it appears to have prevented further compression: through October and November the gap remained in the $14–19 band, rising to around $19 again by late November.

By now the Asia pivot had been in effect for almost a year and the workarounds and new routes were being worn smooth. Other non-aligned allies of Russia were getting into the bonanza on offer from still deeply discounted oil and making it harder and harder to enforce the sanctions regime. One example was the enforcement mechanism for sticking to the $60 price cap was to withdraw a tanker's maritime insurance. Lloyds of London was responsible for 95% of all insurance cover in December 2022, but by the end of 2023 that share had fallen to 65% as Russia and its allies massively expanded their maritime insurance policies for shadow fleet tankers.

No sanctions in 2024

There were no major new sanctions in 2024 or serious attempts to enforce the existing ones. By early 2024, the de facto discount had settled to a remarkably stable spread with discounts of $18.99–19.01 per barrel in January (Brent $76.60, Urals $81.79). Towards the end of January the gap tightened even further to $14.34 on January 29, 2024.

The spring of 2024 marks a structural change. As Russia and its buyers squeezed more value out of the shadow fleet and alternative services, the gap narrowed into the low teens and then single digits. The new distribution system was now not only up and running, but oil professionals were hard at work making it work efficiently.

By March, discounts were mostly between $13.45 and $13.95. In April there was a brief widening – $10.30 on April 19, and $9.01 on April 29 – but from early May onwards you see a clear downward trend. By June 10 the discount had shrunk to $5.51, and by late June and early July it moved in a $5–7 range. On October 3, the spread fell to as little as $2.78 – on a par with the pre-war discount.

At this point it could be argued that the oil sanctions had failed completely and all that had happened is Europe had cut itself off from a cheap and plentiful supply of oil, while Russia had successfully found new customers to replace that demand. And thanks to the changes and cheating, Russia had not sold a single barrel of oil below the $60 oil price cap.

By mid-2024 Urals was trading only a few dollars below Brent – a far cry from the $30–36 gap of 2022 and early 2023. For buyers in India and China, “Russian” barrels were no longer a distressed asset but a highly profitable alternative. While the cost of crude for Indian and Chinese buyers had fallen dramatically, the price of the now “Asian” oil products they were producing -- and exporting to Europe, which was desperate to replace the now missing Russian imports – were the same as always. Refinery profit margins exploded, up ten-fold or more.

Sanctions second attempt 2025

The picture changed again in late 2024 and 2025 as Western governments made a fresh effort to reassert leverage. While the discount stayed relatively modest in late 2024 – bouncing mostly between $5 and $9 per barrel – Washington used its final months under President Biden to unleash a fresh broadside.

On January 9, 2025, Biden announced the toughest oil sanctions ever (6). The package targeted about 180 individual shadow fleet tankers – far more effective than trying to use insurance policies as a lever, as well as placing sanctions on Russia third and fourth largest oil producers: the privately-owned Surgutneftegas and state-owned Gazprom Neft.

That day the discount was $5.19 (Brent $77.53, Urals $72.34). Initially, the gap moved both ways: on January 13 it narrowed to $2.60, suggesting temporary tightness in Urals, but by January 23 it surged to $9.35.

Hailed in the press as a major blow to the Kremlin, the toughest ever sanctions were largely ineffective. Through February and March the spread stayed volatile in a $7–9.5 range, with spikes such as $9.49 on March 6 and $9.27 on March 13, as markets were again pricing in higher risk premia and more complex logistics. But by this time the new distribution system was too well entrenched to see the $30-plus discounts reappear. Moreover, by this time both China and India were getting fed up with the Western bullying, trying to get them to enforce the sanctions and flatly refused to participate.

The EU/UK shadow fleet sanctions (7) on May 19– following the US lead and targeting ships thought to be moving Russian oil outside the cap – highlight just how the new distribution network Russia had built up in Asia had become. On the day of the EU shadow fleet sanctions, the discount was $6.97 (Brent $65.54, Urals $58.57) and remained in the $5–8 range in the following weeks. On June 23, the discount even went negative for the first time since the war started with Urals becoming more expensive than Brent (Brent $71.48, Urals $72.18) to produce a negative $0.70 “discount.”

Frustrated by repeated failure, the EU ramped up its efforts again with the eighteenth sanctions package (9). Oil prices had fallen as OPEC ramped up production and the $60 price cap was by now meaningless as Urals was regularly trading at below that level, meaning anyone could legally carry as much Russian oil as they wanted to.

Brussels responded by introducing a new floating oil price cap on July 17 this year to make sure whatever Russia earned from oil exports was always less than what the market was prepared to pay – 15% less than the previous six-month average Urals price.

A floating price was a clever idea to close a loophole – and it made no difference at all. On the announcement date the discount was a modest $4.09. For the next several weeks it drifted in a $3–5 band, reaching $2.84 by July 31 and $3.26–3.81 in early August. The failure of the floating rate only highlights once again the overall failure of the oil sanctions regime.

Trump's oil sanctions

The final twist in the saga was “Trump’s Rosneft & Lukoil sanctions” (10) on October 10. Since taking office, US President Donald Trump had imposed no new sanctions on Russia whatsoever, as he worked to cut some sort of mineral deal with Russian President Vladimir Putin, using the war in Ukraine as leverage. Biden had targeted the third and fourth largest oil companies; Trump went for the two biggest: state-owned Rosneft and privately-owned Lukoil, which together account for around half of all Russia’s oil production and exports.

On that date of the announcement, the discount was still relatively narrow at $4.41, but in the weeks that followed, as the November 20 enforcement date approaches, the market has reacted. The discount has blown out once more, but to more modest levels than in 2022 and 2023. By November 10, the discount jumped to $9.14 as traders and refiners demanded a far steeper price concession to handle crude from the sanctioned champions.

China has already said it will simply ignore the new sanctions and continue to import Russian crude. India has been a little more cautious and suggested that it may seek replacement crude, but so far imports have not fallen.

Analysts that have been following the saga don’t believe Trump’s sanctions will have much impact as the system will find more workarounds in a few months as it has at each step of the story. Leading oil analyst Sergey Vakulenko called the sanctions “symbolic” in a recent paper, arguing that as the sanctions target the two oil companies by name, and not the oil they produce, it was a simple matter to sell that oil to a trader or intermediatory and dodge the sanctions entirely. By this logic the discount of Urals to Brent should start tightening again in the next few months and will be a good indicator of just how effective the sanctions are.

Nevertheless, the various rounds of sanctions have cost the Kremlin money by forcing it to offer discounts and driving up costs. The Russian oil business is much less profitable than it was, but the Kremlin doesn’t care.

US sanctions are impacting Russian oil revenue, with further measures under consideration, according to statements from the White House on November 19.

The US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) reported that initial analysis of the sanctions announced on October 22 indicates their effectiveness in reducing Russia’s revenues by lowering the price of Russian oil and subsequently limiting its ability to finance the war in Ukraine. According to OFAC, several major Russian crude grades have been trading at multi-year lows, and nearly a dozen significant Indian and Chinese buyers have suspended Russian oil purchases scheduled for December delivery.

Analysts anticipate that China’s seaborne imports of Russian crude could decrease by 500,000-800,000 barrels per day this month, representing a 65% reduction from typical levels. Additionally, the surplus of Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) crude has resulted in a $4 per barrel discount for Chinese buyers, compared to a $0.5 discount at the end of October. Meanwhile, India's state-owned refiners have finalised their first long-term agreement with the US to import 2.2mn tonnes of LNG in the coming year, concurrent with ongoing trade negotiations between New Delhi and Washington aimed at reducing tariffs imposed in response to Russian oil imports.

The Kremlin shook off all this bad news. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said on November 19 that Russia will adapt to US sanctions within two months.

"It's the market, I can't say… You can only look at how it was in the previous period. In the previous period, the discount recovered to a minimum level," Novak said and Vedomosti reported.

Putin is not interested in maximising profits at state-owned enterprises. While he is fighting the war in Ukraine, he is simply interested in generating enough revenue to meet his social spending obligations and funding the military machine.

Follow us online