One year on: laundromat countries allow Russia to dodge oil price cap sanctions

While it is clear that the sanctions have not reduced the Kremlin’s resolve for war one year on, a CREA analysis revealed that the EU oil import ban and G7 price cap have cut the country’s export earnings from oil by only 14%, costing Russia a total €34 bn in export revenue – not enough to make a war in Ukraine unaffordable.

“The price cap has had an impact but has failed to live up to its potential. The price difference on Russian oil and benchmark global oil has declined steadily since early 2023, showing that the effectiveness of the sanctions has fallen. Consequently, the impact of the sanctions largely took place in the first half of 2023,” says CREA.

“The declining effect of the sanctions is due to the failure of G7 and EU governments to enforce and strengthen the price cap. This failure has enabled Russia to sell its oil above the price cap level, while increasing export volumes to new willing buyers that are not imposing sanctions,” CREA added.

The main hole in the sanction’s regime is oil products refined from Russian crude are legally exported to price cap imposing countries. This “refining loophole” provides an outlet for Putin’s oil exports.”

CREA analysis shows that the sanctions impacted Russian oil export revenues heavily for the first half of the year – peaking at losses of €180mn per day in the first quarter of 2023 – after the twin embargos of December 5 2022 and February 5 2023 were imposed. In January 2023, Russia saw a significant 45% month-on-month decline in overall fossil fuel revenues, with crude oil alone experiencing a 25% decrease.

But after Russia’s Ministry of Finance (MinFin) remade the tax regime and exports by ship started, the Russia’s budget went back into profit in August and oil revenues are now higher than they were on the eve of the war. As bne IntelliNews reported, oil sanctions are a spent cannon.

“A failure to enforce, strengthen and consistently monitor the price cap has allowed Russia to undo the impact in the second half of the year. Revenue losses shrank to €50mn per day in the second and third quarters, and then recovered to €90mn per day in the last quarter of the year,” says CREA. “The effectiveness of the sanctions has fallen due to insufficient monitoring and enforcement of the oil price cap policy that enables Russia to sell its oil at prices above the set cap level.”

Laundromat countries

As bne IntelliNews reported a year ago in a piece about sanctions leakage, Russian refineries in the EU legally produce oil products using Russian crude oil to enter countries imposing sanctions and Russia.

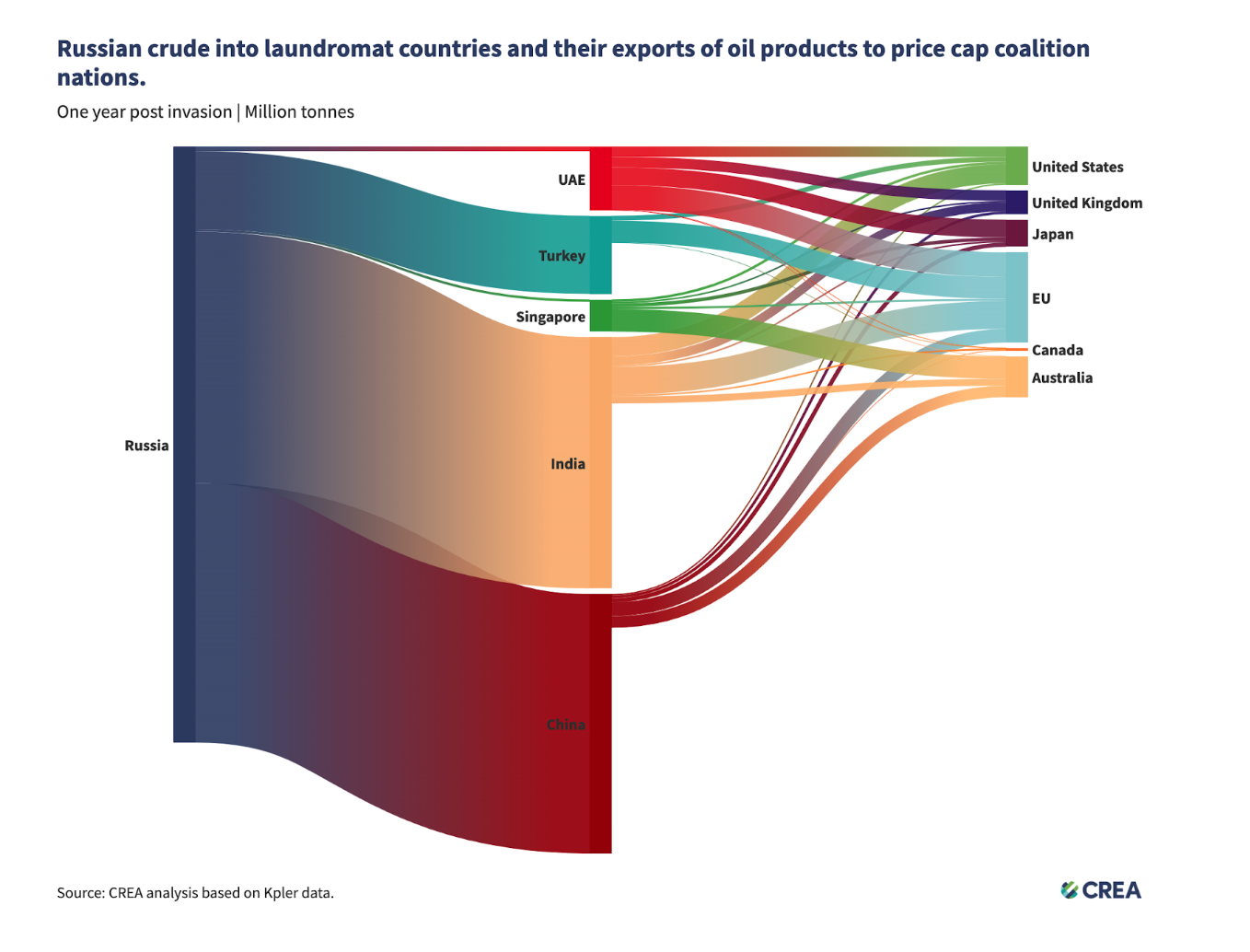

Russia has also sold crude to countries outside of the regime that then ship the oil products back to Europe, creating a second loophole. China and India and the main culprits in the latter scheme.

The upshot has been Russian oil companies legally sold their own crude to their European-based refining subsidies at very depressed prices that also reduced their tax bill to the Russian government, which is why the tax revenues fell so heavily in the first half of 2023. That crude was then refined and sold on to the EU market at normal prices.

The profits accrued to their European subsidiaries and were not sent back to Moscow. In this way a slush fund, worth up to an estimated $140bn of unsanctioned money, has built up overseas in the last year, that is under the control of the oil companies. The Kremlin may not know where this money is, but they do know who has it and roughly how much it is worth and as such can use it to buy sanctioned goods legally.

A prime example of this is the Neftochim Burgas refinery in Bulgaria that is owned by Russian company Lukoil. A CREA investigation with partners Global Witness and the Center for the Study of Democracy found that since the implementation of the EU’s import ban on Russian crude oil, Burgas has imported Russian crude oil worth over €1.1 bn in tax revenues to the Kremlin, using the refining loophole.

At the same time Asian countries outside of the sanction’s regime, what CREA calls the “laundromat countries”, are paying Russia market prices providing more money Russia can use to buy sanctioned goods.

“This is currently a legal way of exporting oil products to countries that are imposing sanctions on Russia as the product origin has been changed. This process provides funds to Putin’s war chest,” says CREA. “Laundromat countries’ exports of oil products increased 80% in value terms and 26% in volume terms (selling an additional +10mn tonnes) to price cap coalition countries, but only rose 2% (or +2.9mn tonnes) to non-price cap countries in the year since the invasion on prior year levels.”

In parallel to rerouting Russian oil exports almost completely from the EU to Asia, Russia’s Ministry of Finance (MinFin) was working hard to remake the tax code to recover its oil revenue. Pre-war the value of oil exports was benchmarked to the price of Russia’s Urals blend that was mostly sent from the Baltic port of Primorsk to Rotterdam and then on to the rest of Europe. But this trade collapsed due to the embargo and the price of Urals blend tumbled, taking the tax revenues down with it.

Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov remained unperturbed at the start of 2023, predicting that oil revenues would recover in the second half of the year.

1023 Russia OOTT Federal budget oil revenues, in ruble billion KSE

He was right. Oil taxes are now benchmarked against the price of Brent, minus a discount, and Russia’s budget went back into profit in August. Instead of the 3-4% budget deficit most analysts were predicting for the year at the start of this year, now Siluanov is confidently predicting a deficit of less than 1% of GDP – despite the massive spending on the war effort.

Counterparties

While exports to China and India have soared, counterintuitively the EU remains the biggest importer of Russian crude, whose imports amounted to €17.7bn.

Australia purchased €8.0bn worth in the 12-month period since Russia’s invasion, followed by the USA (€6.6bn), the UK (€5bn) and Japan (€4.8bn). The highest proportions of imported oil products into oil price cap coalition countries were diesel (29%), jet fuel (23%) and gasoil (13%), according to CREA.

1223 GLOBAL Russian oil laundromat exports of refined products to sanction coalition countries CREA

The Indian port of Sikka is the biggest oil product export port to the price cap coalition countries, and the largest importing port in the world of seaborne crude oil from Russia. The port serves the Jamnagar refinery. €2.7bn of petroleum products have been exported from that location to price cap coalition countries since December 2022 to February 2023.

China’s monthly exports of oil products to Europe and Australia spiked in late 2022, far above historical levels. In the lead-up to sanctions on Russian oil, China significantly increased its oil products exports, reaching 2.9mn tonnes in fourth quarter of 2022, which was 150% higher than the quarterly average in 2022.

Overall, the PetroChina Dalian refinery in China is the largest recipient of Russian crude oil in the world, due to a pipeline connection to Russia. The main export destination for oil products from Dalian is Australia.

Just over half (56%) of Russian crude oil shipped to laundromat countries has been transported by vessels owned and/or insured by the price cap coalition countries since December 2022 up until the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“This share is three quarters (74%) for oil products exported from laundromat countries from December 2022 until the anniversary. This illustrates the coalition’s strong leverage to ratchet down the price cap level as well as taking action to ban refineries buying Russian crude to refine it and sell the products to sanctioning countries,” says CREA.

In the year following the start of the invasion, seaborne imports of Russian crude oil into China, India, Turkey, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Singapore increased by 140% in volume terms, compared with the 12-month period before the invasion. The total value of their imports was €74.8bn over the twelve months, and since the EU crude oil ban until one year after the start of the war, these five laundromat countries have made up 70% of Russia’s crude oil exports.

CREA, along with many others, recommend tightening the enforcement of the oil cap sanctions as Russia still relies on many EU ships to transport its oil, and halving the cap from $60 to $30.

“The most important way to cut Russia’s export revenues further would be to drive down the oil price cap. A price cap of $30 per barrel (still well above Russia’s production cost that averages $15 per barrel) would have slashed Russia’s revenue by 49% (€59 bn) since the sanctions were imposed until the end of October,” says CREA.

Follow us online