Paris Agreement’s carbon budget all spent in growing number of developed countries

A carbon emission budget built into the 2015 Paris Agreement to buy the world some time before environmental catastrophe strikes has already been exhausted by some of world’s biggest carbon emitters and we are burning through what remains far too fast.

The US has already used up all its carbon budget and has overspent its “carbon budget” by roughly 346 gigatonnes, according to a little noticed analysis published by Scientific American last year. Russia, the EU and the world’s highest per person emitters (Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait) have also exceeded their budgets and are now in “carbon debt”, spending the carbon budget surpluses of other countries, according to the analysis.

NASA has released a new visualization that shows copious amounts of carbon dioxide wafting off the Earth and swirling through the atmosphere.

The video shows how concentrations of the gas move across the planet, driven by wind and atmospheric circulation, from January through March 2020. The US, in particular, stands out as a major source of emissions. In 2021, the US accounted for over 12% of global emissions, only outdone by China, which accounted for just under 33%.

But the other big carbon-emitting countries like China and India still have large carbon budget surpluses, a credit they have been using to build coal-fired power stations needed to fuel their fast economic growth but are both also investing heavily in renewable energy. China has become the global green energy champion. Two-thirds of the world's new wind and solar power plants have been built in China. India was also the world’s second biggest producer of green energy in 2023.

The Paris Agreement allowed for a budget of carbon emissions for a 50% chance of staying under the 1.5C increase of temperatures above the pre-industrial baseline.

The remaining global CO₂ budget to limit global warming to 1.5°C was set at 500 gigatonnes of CO₂ in the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report of 2021. For a 50% chance of keeping temperatures below the Paris upper limit of a 2C rise then the carbon budget is 1,350 gigatonnes.

At the current rate of emissions, an average country will use up its share of about 50 gigatonnes per country in seven years from now.

And the 1.5C target is increasingly likely to be missed as the international community is burning through its carbon budget far too fast. The world has already used up between half and four-fifths of its carbon budget, according to different estimates, and at most 200 gigatonnes of the carbon budget is left in 2024, as tracked by the Carbon Clock.

As bne IntelliNews reported, despite the growing crisis and disaster seasons of extreme weather, concentrations of three most dangerous greenhouse gases (GHGs) – CO2, methane and nitrous oxide – have climbed to all-time highs.

Put in other terms, scientists say that the CO₂ concentration hit a new record of 399.4 parts per million in 2015 when the Paris Accords were signed. Since then, the concentration has risen to 427 parts per million as of April – a 7% increase.

The world is emitting some 40 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year, which at that rate means the entire carbon budget will be depleted in 2029. If temperatures are to rise by less than 2C, the upper limit set at Paris, then there is a carbon budget enough for another 22 years.

To retain the 50% chance of a 1.5C limit in temperature rises, emissions would have to plunge to net zero by 2034, far faster than even the most radical scenarios on the table and 15 years earlier than the EU’s Fitfor55 carbon reduction plan to get to carbon zero by 2050, one of the most comprehensive schemes of all.

Carbon debt

The world is on course to significantly overspend this budget by emitting way more carbon dioxide than has been budgeted for by the Paris Agreement. Global temperatures are already a little more than one degree centigrade warmer now than in preindustrial times and last year was the hottest on record, with every month seeing temperatures 1.5C above the industrial baseline.

The last United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the gold standard for measuring climate change, estimates that between 1850 and 2019 humans emitted about four fifths of the amount of CO₂ that would give us a 50:50 chance of keeping the world’s temperatures from rising by more than 1.5C.

This carbon budget does not include other greenhouse gases (GHGs) or the cooling effect of aerosols, among other factors, which is a problem. As bne IntelliNews reported, the climate models are wrong, as they don’t take account of aerosols removed from the atmosphere, which means more direct sunlight is falling on the surface of the planet, increasing the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) and heating the earth faster than was anticipated in 2015, when the Paris Accord was signed. Moreover, water vaporisation is also rising fast due to the hot weather; the vapour is also a GHG that threatens to accelerate global warming and is already causing torrential storms and flooding.

Estimates of how much is left in the budget vary but agree that there is at most some 200 gigatonnes of emissions still available to spend and remain under the goal of a 1.5C temperature rise, and even that is an overestimation.

The world is currently producing about 40 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year and instead of slowing, global CO₂ emissions have accelerated and we are emitting more CO₂ than ever before. Study after study in the last year has called for drastic action, and none has been taken. Politicians and entrenched economic interests have worked hard to block all emission cuts.

A new 108-page UN report issued just before last year’s COP28 summit found that nations would have to cut their emissions by an eye-popping 42% by 2030 if the world has a chance of meeting the Paris goal.

The COP28 summit, hosted by Sultan al-Jaber, also head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, was a cop-out. The final agreement called for “accelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power,” and ramping up the use of “abatement and removal technologies…particularly in hard-to-abate sectors”.

A “phase-down” of unabated coal is not a “phase-out” and “unabated” means that fossil fuels will continue to be burned, but the emissions are supposed to be buried or sucked out of the air by a “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) technology that is currently not available.

Who’s to blame

But not everyone is guilty of doing nothing. China has emerged as the global green energy champion. Although it remains the world’s biggest emitter of GHGs, it still has a large carbon budget surplus and is leading the world in the roll-out of renewable energy capacity.

China emitted 11.4 gigatonnes in 2022, followed by the US with 5 gigatonnes. India, Russia and Japan are next in the top five ranking with 2.8, 1.7 and 1 gigatonnes respectively. The EU collectively emitted 3.6 gigatonnes in 2022, according to the European Commission, ranking it third as a group and slightly ahead of India.

World’s biggest emitters of CO₂ in 2022

World’s biggest emitters of CO₂ in 2022

However, China still has a big carbon budget surplus and it generated more green energy in May alone than any country in the world generated in all of 2023, and accounts for two-thirds of the world's new wind and solar power plants. China has invested so much that it is, uniquely amongst the big countries, already close to peak emissions – well ahead of the 2030 deadline.

India is another of the world’s big polluters, but again it also has a large carbon budget surplus and has also thrown itself into green energy: India was the second biggest producer of green energy in 2023, after China.

The EU has enthusiastically embraced the green transformation with its Green Deal and Fit for 55 programmes, but the EU has already burnt through its entire carbon budget and is in carbon debt, according to a little noticed paper in Scientific American released last year

But the worst offender is the US, which is second to China, but already spent its entire carbon budget, double its allotted allowance, exceeding its budget by 350 gigatonnes in 2023, according to Scientific American.

The US’ lavish emission of CO2 means that while developing countries such as India and China are allowed to use more dirty fuels like coal to power their fast catch-up growth, their surplus carbon budget should have been enough to allow for this transition. Now the US is spending their carbon budgets for them. That has put pressure is on all the other countries of the world to make deeper cuts now – and without compensation from the US.

“You’re sort of entitled to it, but you can’t burn it for the sake of the Earth,” says climate scientist and IPCC author Piers Forster of the University of Leeds in England.

There have been multiple calls on the US to cut emissions, but while in office former US President Donald Trump took the US out of the Paris Agreement altogether and promises to do the same again if he wins office this November.

The US is the world’s biggest carbon debtor with China and India still in comfortable carbon surplus

Per capital emissions progress

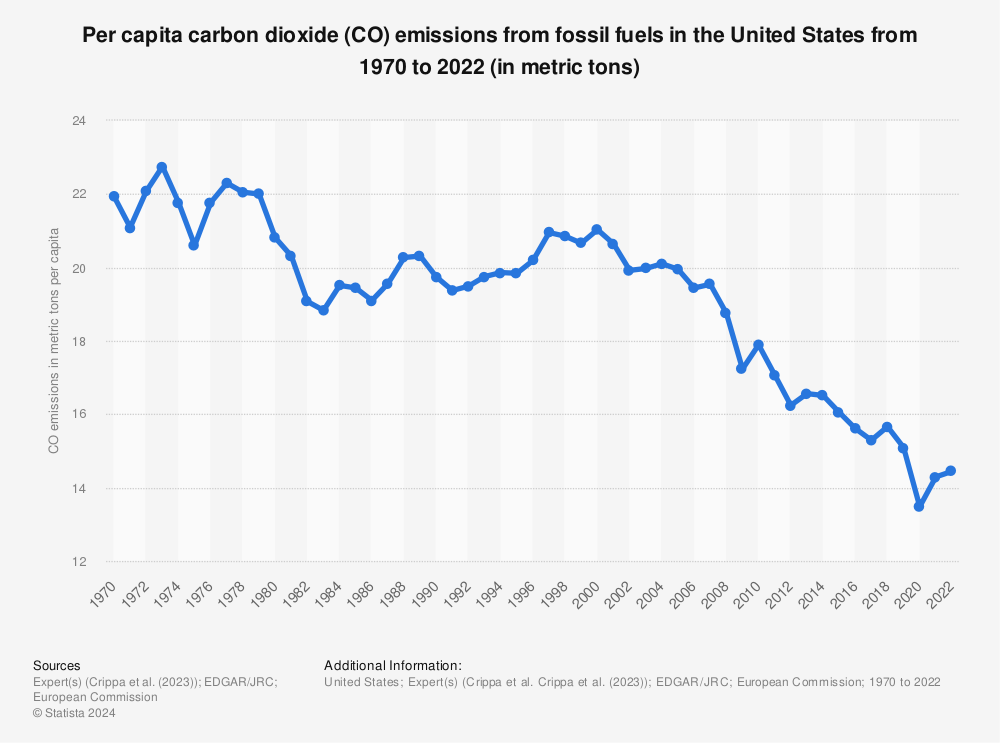

How many people you have and how industrialised your country is goes into calculating the amount of carbon credit each country is assigned and real progress in reducing the per capita emissions has been made over the last two decades, even in the US.

The Paris Agreement specifies in Article 4.1 that developed countries will have a proportionally higher reduction in emissions as it states "peaking [in GHG emissions] will take longer for developing countries", and states repeatedly that decisions will be taken according to "the principle of equity". This principle of equity is usually taken to mean that the residual global CO₂ budget of approximately 50 gigatonnes per country will be divided between nations as an equal share per person.

So, if a country has CO₂ emissions per person that are double the world average, it has to cut emissions twice as quickly as the average. If it cuts emissions only as fast as the average, it would take double its fair share of the CO2 budget.

The US has released more heat-trapping gases to date than either China or India, the world’s two most populous countries. But both China and India are relatively latecomers to industrialisation and were allotted a bigger carbon budget as a result.

In 1973 US per capita carbon dioxide emissions were 20 times more than China’s and 66 times those of India’s. By 2000 when global warming had arrived on the agenda, the US per person emissions had dropped to just over 21 tonnes per year and since then has fallen further to 14.4 tonnes as of 2022. US per capita fossil CO₂ emissions have dropped by more than 25% since 1990.

Find more statistics at Statista

By 2000, China’s and India’s per capita emissions had risen to 2.9 tonnes and 0.9 tonnes respectively – multiple times lower than the US.

In 2021 China was producing 11.47 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year, which means it would have taken 15 years to match the US historical contribution, and India’s rate of 2.71 gigatonnes per year means it would take about 135 years to catch up to the United States’ level of historical emissions.

Compare that with a more developed market like the UK, which was producing 8 tonnes per person per year in 2021 (or a total of 0.43 gigatonnes) – nearly double the global average of 4.5 tonnes per person per year.

At that rate, the UK's per capita fair share of the CO₂ budget of 50 tonnes per person was expected to run out six years after 2020, when the budgets were agreed, but it has run out a year early.

India was producing 1.8 tonnes CO₂ per person per year in 2020 – less than half the world average – so India's 50 tonnes per person budget should last another 30 years. Taking advantage of this wiggle room, the government continues to build new coal-fired power plants to fuel its rapid growth, but it has responsibly been investing heavily into renewables at the same time.

If you fudge the target and increase the goal to capping temperature increases at 1.6°C instead of 1.5C, that increases the global CO₂ budget to 150 gigatonnes but that will buy only four extra years at the current global emission rate. And for a high-emission country such as the UK, its per capita share will last an extra two years.

Absolute targets still being missed

While there has been real progress in reducing per capita emissions, in absolute terms emissions are not slowing anywhere near fast enough.

The Paris targets are being comprehensively missed by almost everyone. As bne IntelliNews reported, rather than falling, levels of the three most dangerous human-caused GHGs have risen to record highs. Concentrations of CO₂, methane and nitrous oxide climbed to record levels in the global atmosphere in 2023, contributing ever more to the climate crisis.

In 2019, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations (410 parts per million) were higher than at any time in at least 2mn years. Concentrations of methane (1,866 parts per billion) and nitrous oxide (332 parts per billion) were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years.

Only 11 developed countries have reduced emissions and that group doesn’t include any of the five biggest emitters listed above. Even amongst the 11 that have reduced emissions, none are anywhere close to hitting their Paris accord obligations, according to a study published in the Lancet last year.

The situation has become even worse than predicted by IPCC, as it appears the climate models are wrong, as they don’t take into account the removal of aerosols in the last four years that used to reflect sunlight away from the planet’s surface. As a result, the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) has increased, as in addition to the warming effect of GHGs, more sunlight is making it to ground level and also heating the planet.

Last year saw temperatures above 1.5C every month of the year for the first time, although technically the Paris Agreement threshold of 1.5C has not yet been breached, as long-term average temperatures have to be above 1.5C, counting out natural variability caused by things like the El Niño weather phenomenon. Removing natural variance fluctuations, and last year’s adjusted average temperature was 1.3C above the pre-industrial baseline.

There is an 80% likelihood that the annual average global temperature will temporarily exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for at least one of the next five years, according to a new report from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO).

As a result of increasingly high temperatures extreme weather events are already becoming more common. This summer there have already been 11 cities with temperatures of more than 50C, on the edge of what humans can survive. More are expected to join the “50C club” later this year. In July, Death Valley, California set a new all-time world record for the hottest reliably measured temperature in Earth’s history as the mercury rose to over 54.5C, breaking the previous record of 54.4C set only two years ago.

Scientists worry that large swathes of the planet will be made uninhabitable in the coming decades that will cause billions of people in places like Africa, India and China to migrate north in search of more temperate climes.

But at the current rate of emissions reduction, it will take more than 200 years for the developed world to reach carbon-zero, unless the leading economies of the world commit to make real and deep structural changes and invest trillions of dollars over the next few years. The carbon clock gives us only six more years to make these changes to avoid disaster.

Follow us online