Sanctions leakage: pipes and tankers

After about two months of problems caused by oil traders self-sanctioning at the start of the war, Russia’s oil exports have largely recovered and replaced most of the fall in demand in Europe with new buyers in Asia. The challenge Moscow now faces is how to get the oil there. There are two options: by a limited number of oil pipes, but most goes by ship.

Despite its proximity, Russia sent 75% of Russian oil exports to Europe by tanker before the war and tankers continue to carry the bulk of the oil exports today. While the West has not banned Russian oil exports as it remains very reliant on Russian oil imports, it did ban ships from carrying the oil as part of the sixth package of sanctions, but to little effect. That ban is due to be strengthened when the EU will ban imports of Russian crude completely on December 5 – or at least attempt to limit the money the Kremlin makes with an oil price cap – and the more widely spread refined product on February 5, but it remains to be seen if these bans can be made to stick.

The main problem with the sixth package restrictions is that because shipping is such a large part of the Greek economy – an EU member – it was given an exemption. Not only did Greece continue to transport Russian oil, it saw an opportunity to make some extra money. Greek ships’ share of Russian oil transport has grown from 35% pre-war to 55% now, according to a study by Institute of International Finance (IIF).

The sixth package of sanctions threatened secondary embargoes on international shipping firms and insurance companies to prevent Russia sending oil by sea. But between Greece’s exemption and the fact that India certified the entire Russian fleet as safe, which then got Russian insurance cover, the sanction threat didn't work. What remains to be seen is when the West tightens the noose on Russia’s oil exports in December if multiple oil transport leakages can be plugged.

Tanker fleets

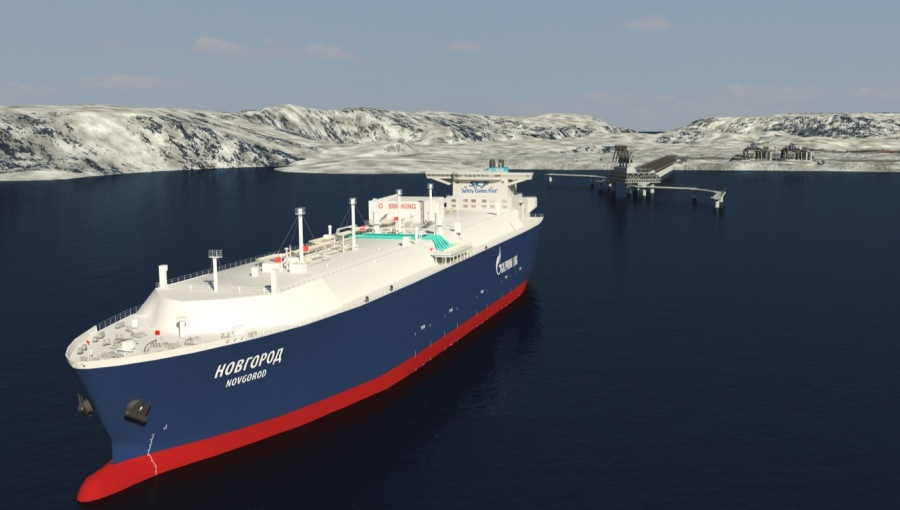

In the last five years Russia has invested very heavily into expanding its fleet of ships by pressing its huge shipyards into service and it has significantly expanded its shipping capacity that covers much of the shortfall.

According to S&P Global Commodities at Sea, Russia was typically shipping around 30mn barrels of refined products to Europe on a monthly basis, based on last year's activity. From these volumes, around 20mn barrels each month referred to gasoil/diesel, equal to up to 700,000 barrels per day (bpd).

It has a well-developed ship building industry much of which is concentrated in St Petersburg, Murmansk and Vladivostok. In recent years Russia has been investing into advanced nuclear-powered icebreakers as the Northern Route that runs along the northern coast opens up – a much shorter route connecting Europe and Asia. Russia has also developed a line in floating nuclear power stations that it intends to sell internationally. But it will take years to build enough large oil tankers to replace the international fleet it currently relies on to transport oil.

Most of Russia’s fleet of tankers is owned and run by the state-owned Sovcomflot shipping company, one of the global tanking leaders. As of May 2022, the company owned 122 vessels: 52 Aframaxes oil tankers, 9 Suezmaxes and 34 oil products tankers, as well as 10 natural gas carriers and 10 icebreakers. In March Sovcomflot was added to the UK sanctions list and it was later targeted by the US and Canada too. The fleet is currently insured by the Russian company Ingosstrakh.

Russia sent 53mn barrels a month to Europe in 2021, with 84% of this carried on the smaller Aframaxes and most of the rest carried on the bigger Suezmaxes, the largest tanker that can navigate the Suez Canal.

The switch of Russian oil shipped to China and India instead of Europe is estimated to require around 30 Aframaxes (including those employed for lightering), 50 Suezmaxes and most importantly more than 40 Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC), which means that Russia has to rely on international shippers for at least two thirds of its shipping needs.

Greeks bearing gifts

This December the West intends to impose an oil price cap scheme on Russia. Two things need to happen for it to work. Firstly, India and China, as the biggest importers of Russian oil, both need to join the scheme and that is unlikely to happen. Secondly, Greece needs to be persuaded, or forced, to stop working with Russia.

One of the difficulties of working out who is really carrying Russian oil is the ease of changing a ship’s flag. It is hard to sanction a ship if you don’t know who really owns it.

IIF has built a database to track the movement of oil tankers out of Russian ports. The innovation is that it has also built a webcrawler that can identify who the ultimate beneficial owner of the ship is.

“We have built a new database tracking the movement of oil tankers out of Russian ports. The innovation in our data is that we identify the true ownership of these vessels, which is often difficult because they are registered and flagged all over the place. We trace the ultimate owner through shell companies as needed, which provides some perspective on who has been helping to ship Russian oil around the world. The conclusion from this work is that tanker capacity out of Russia has been robust overall,” Robin Brooks, managing director and chief economist at IIF, said in a note. “It turns out that Greek-owned ships are 55% of total tanker capacity, compared to 35% in previous years.”

Many Western companies look like they self-sanctioned and withdrew from shipping Russian oil, while Greek-owned tankers picked up the slack. Between March and August 2022, IIF estimate that Greek-owned vessels not only failed to avoid Russian oil; they actually boosted their capacity to help helped Russia secure a record current account surplus of $166bn.

Volumes of oil exports of crude from Russia this year are not only not depressed this year in August, but they are at record levels. Russia is exporting more oil today thanks to the war than it has ever exported before, says IIF.

“Comparing the volume of tanker traffic out of Russia in August 2022 to the same month in past years then in 2022 oil exports are at an all-time high,” IIF concludes. “The compositional shift to Greek-owned vessels has more than offset any self-sanctioning effects.”

(chart: tanker tariff from Russia has been robust, with a big shift in composition;

chart: robust export volumes are due to Greek vessels, which account for 50% of capacity;

chart: tanker traffic is robust compared to last year, helping boost the current account).

Indian safety certificates

The West controls some 90% of the maritime insurance business through giant companies such Lloyds of London, but another piece the puzzle is that ships need to be certified safe before they can get insurance. And India has already blown a huge hole in attempts to prevent Russian ships getting these certificates.

An Indian insurance company agreed to offer Russian tankers safety certification to a Dubai-registered subsidiary of Russia’s biggest ship operator Sovcomflot on June 23. That will allow Russia to export oil to Indian even if the Western insurance sanctions are put into effect, although the Russian fleet is not big enough to carry all of the 8mn bpd that Russia exports. However, it is big enough to deliver the approximately 1mn bpd that India is currently buying.

Certification by the Indian Register of Shipping (IRClass) could well be accepted by Russia’s other nonaligned customers in the developing world, most of which have refused to join the Western sanctions. As bne IntelliNews reported, the enthusiasm for the West’s sanctions beyond the G7 countries is only lukewarm.

And there are other certifiers out there that Russia can turn to. India's ship certifier is one of 11 members of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS), top-tier certifiers that account for more than 90% of the world's cargo-carrying tonnage. The Russia Maritime Register of Shipping was also part of the group until March, when its membership was withdrawn following a vote by 75% of IACS's members. However, only four of the 11 members (UK, Norway, France, and the US) have withdrawn their services from Russian ships due to sanctions, while the rest could in theory offer certificates.

As bne IntelliNews reported in an oil price cap Explainer, experts say that using maritime insurance as an enforcement mechanism without India and China’s participation will be very difficult to make work. Although the largest insurers are in London, Russia has at least two very large insurance companies that offer maritime products, which Russian ships are already using and which is already being accepted by customers like India and China.

Sovcomflot's chief executive told reporters in July that the group had insured all its cargo ships with Russian insurers and the cover met international rules. Reuters reported that the Russian state-controlled Russian National Reinsurance Company (RNRC) has become the main reinsurer of Russian ships, including Sovcomflot's fleet. RNRC is controlled by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), which has recently recapitalised the company to RUB300bn ($6bn) from RUB71bn and hiked its guaranteed capital to RUB750bn so the firm had adequate resources to provide reinsurance under international maritime law.

Indian authorities have also accredited the privately owned Russian insurance giant Ingosstrakh as an insurance company for shipping oil, which means vessels the company insures can enter Indian ports.

Oil cocktails

Using tankers to transport oil also facilitates the practice of creating sanctions-dodging “crude cocktails” where producers blend various crudes or refined products, so they are no longer “Russian.” Early in the sanctions regime international oil major Shell got caught out for buying the “Latvian blend” of oil which was 49% Russian and 51% locally sourced oil, technically reclassifying it as “Latvian oil” and so avoiding sanctions.

Following a scandal, in April Shell has backtracked and now explicitly demands in trading contracts that a blend contain no Russian oil at all. Indeed, the company has cut all ties with Russia and is trying to sell what assets it has left in the country. Other European companies including TotalEnergies, Repsol and BP also stopped buying any refined products blended with Russian content.

Transporting oil by ship also allows crude cocktails to be mixed at sea by ship-to-ship transfers of oil. Russia has already played this game in reverse after it secretly exported oil from Venezuela after the US slapped sanctions on the South American country. One of the mechanisms was mid-ocean ship-to-ship transfers between the two nations. Cuba also got caught up in the row after Russia facilitated busting the US sanctions by transporting Venezuelan oil to the Caribbean island state in 2019 to alleviate a fuel shortage there.

More recently, international oil major Exxon got into trouble in August by buying another dodgy cocktail, the so-called CPC blend that is supposed to come from Kazakhstan, via the Capital Pipeline Consortium pipe that runs across southern Russia from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea and on to global markets.

The CPC pipeline carries about four fifths of Kazakh oil exports to the West and is a key part of its export infrastructure that ends at the Russian port of Novorossiysk.

In 2021, CPC shipped 60.7mn tonnes of oil, equivalent to roughly 510mn barrels, through the Novorossiysk terminal. Of that total, 53mn tonnes came from the Kashagan, Tengiz and Karachaganak fields in western Kazakhstan. Another 7.7mn tonnes was delivered by Russian companies. The terminal handles about 1% of global oil supply.

Russian and Kazakh crudes are regularly mixed before being put on ships, but as the Russian share is much smaller, the CPC blend is considered to be Kazakh.

In August it was revealed that Exxon shipped thousands of barrels of CPC blend to the UK, where it has a refinery at Fawley, near Southampton. Exxon has pulled out of Russia but continued to receive a string of shipments of CPC blend since the war began, according to tanker tracking data, reports the Telegraph.

Exxon denied that there was any Russian oil in the CPC blend and claimed it came from its Kazakh joint venture. Exxon is a shareholder in the Kazakh oil joint venture Tengizchevroil (TCO), that is also owned by Chevron and the Kazakh government to work Kazakhstan's giant Tengiz project. The company said that all the oil exported via the CPC pipeline was its own oil from its own field and no Russian oil had been added.

Exxon said in a statement: “Since the invasion, there have been no deliveries of crude with a certificate of origin issued in Russia to our refinery at Fawley – and none are scheduled.”

Ukraine remains suspicious of the CPC pipeline and called on a ban on oil transported by the CPC pipeline as it is very difficult to prevent Russia mixing in some of its own oil with the Kazakh. Oleg Ustenko, chief economic advisor to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy called for a “complete and immediate” embargo on Russian fossil fuels in Europe, “including CPC,” in an opinion piece for the Financial Times, adding: “Business as usual serves only to prolong the war."

Kazakhstan’s use of the CPC pipeline, which is managed by Russian oil pipeline monopolist Transneft, has not gone smoothly. Russia shut down the pipeline for the fourth time in August in what many saw as Moscow punishing Astana for insufficient loyalty to the Kremlin, although the government reported on September 7 that the oil flows were proceeding as normal.

Pipeline leakage

The bulk of Russia oil, even before the war, was exported by ships but there are two pipelines that deliver oil to both Europe and China.

Some Russian oil exports to Europe have been sent via the Druzhba (“Friendship”) pipeline that was built in the 1970s and first connected to Austria, before being extended to Germany, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia and Bulgaria, which collectively accounted for 8% of Russia’s oil exports in 2021.

The passage of the sixth package of sanctions in the summer of 2022 was extremely difficult to pass. Hungary, Bulgaria and Slovakia, all connected to the legacy Druzhba oil pipelines built in the 1970s, refused to end imports of Russian crude for both political and economic reasons. In the end a compromise was thrashed out but despite Brussels' best efforts, Russia continues to export oil to Europe, albeit at reduced volumes.

The pipeline's current capacity is 1.2-1.4mn bpd with the possibility of raising this to 2mn bpd. As of January 2022, about 750,000 bpd of crude oil was supplied through the Druzhba network, with 50% destined for Germany, followed by Poland with 16%, Slovakia with 13.5%, Hungary and Slovenia with 11% and Czechia with 9.5%, according to IHS Markit.

The second pipeline runs east and is much newer. The Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) to China was built in 2006-2009 and now carries about 800,000 bpd, about half of China’s Russian imports of oil. It draws on oilfields in western Siberia and has been running at full capacity all summer. An additional 1mn bpd of capacity is supposed to be added to ESPO this year.

While the volumes of oil exported by the Druzhba pipeline to Europe could be cut to about a quarter of normal, those to China will almost certainly stay the same or even double significantly offsetting the European fall in demand.

The sanctions leakage has been significant. Germany joined the direct embargo but continues to import Russian oil indirectly for its big refineries near Berlin, buying oil arriving in the Polish port of Gdansk but also availing itself of the “crude cocktails” of oil blends that started appearing on the market, according to reports.

While the G7 finance ministers have set themselves the task of cutting the Kremlin off from its oil export revenues, with so many leakages already built into the system their effort can at best be only partially successful. Whether this is enough to cause the Kremlin enough financial problems to end the war in Ukraine early or cause the Russian economy to collapse remains to be seen.

Follow us online