This winter’s gas crisis in Europe is already over before it began

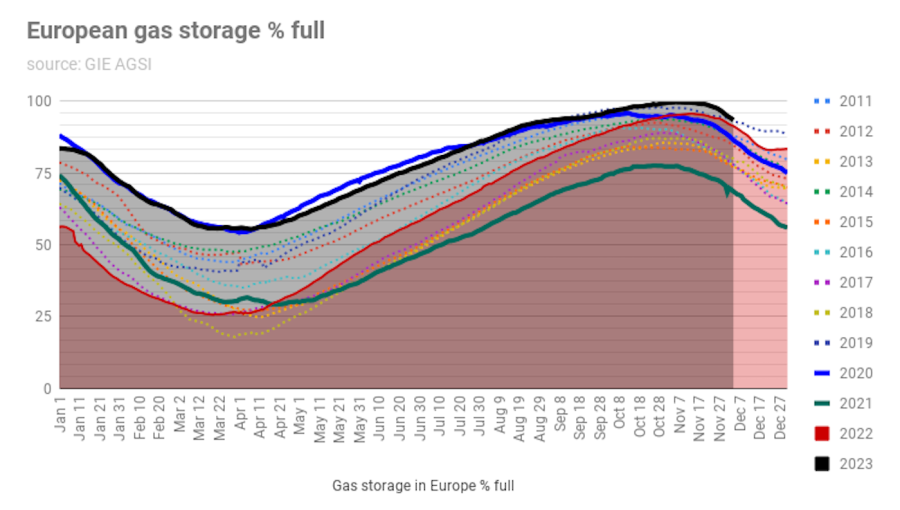

Europe went into this year’s heating season, which started on November 7, with its tanks full to bursting; the EU gas storage tanks were close to 100% full as the weather turned cold. (chart)

Moreover, Europeans have been delaying taking gas out of the tanks as demand exceeds imported piped gas via Ukraine and Turkey by continuing to buy imported LNG from places such as the US and Qatar in order to spin out the excess reserves in the tanks for as long as possible, until it becomes clearer just how cold this winter will be.

Europe’s underground storage tanks were 99% full on November 19, at which point the gas flows reversed from in to out, but by December 4 they were still 93.3% full compared to 91.3% full on the same day in 2022 and 68.5% full in 2021.

The gas tanks by themselves cannot supply Europe with more than a large fraction of the gas it needs over winter. The system was designed so that in the summer months when demand is low the excess piped gas is stored, but in winter the demand rises and that extra gas is withdrawn from the tanks. However, the stored gas only covers the excess demand due to colder weather, not the whole demand. The upshot is in cold winters the tanks can struggle to cover a really big excess demand.

And in the last two years the whole structure of the energy market in Europe has changed. The gas tank system was built on the assumption that Russia would continue to supply gas steadily to Europe throughout the winter; in the warm months the excess is stored and in the cold months it is burnt. What has changed is the approximately 150bn cubic metres of gas that Russia used to deliver has fallen to an estimated 25 bcm this year. The tanks do not, and cannot, hold the missing 125 bcm that has disappeared from the system since the Nord Stream 1&2 pipelines were destroyed last September.

Last year Europe imported a surprise 130 bcm of LNG to cover the shortfall, and this year LNG remains the most important alternative source of gas to cover Europe’s heating and power needs. However, LNG remains an immature business and it is not clear there is sufficient production to meet the LNG needs of both Asia and Europe for gas if demand in both markets is high at the same time.

The gas consumption tends to peak as the onset of colder weather in the Northern Hemisphere forces households and office buildings to turn up the heat. But you wouldn’t get that impression from looking at gas prices this year, with European futures falling to the lowest since early October, reports Bloomberg.

After creeping up from $400 per thousand cubic metres in August to $600 in November, traders' fears of shortages in Europe and Northeast Asia have all but disappeared, bringing the future prices of gas down with them.

One of the factors pushing prices down is poor economic performances of both China and the EU. Weak industrial demand, particularly in China and Germany, has taken the pressure off fuel supplies. In 2022, China’s economy was still under a COVID lockdown that depressed demand for gas and while those restrictions were lifted this year, the Chinese economy has failed to bounce back very strongly.

In Europe, industry is also depressed thanks to the on-going effects of the polycrisis, and as bne IntelliNews recently featured, the boomerang effect of sanctions on Russia means that all the major EU markets bar Spain saw negative growth in the third quarter of this year and are only expected to put in very amnesic growth in the fourth quarter. Germany, the biggest economy in Europe, is already in recession.

The combination of plenty of reserves and low demand is that the world looks set to get through its second war-winter without any major drama, even in the event of record-breaking cold blasts.

Temperatures have already plunged, with Russia seeing the most snowfall in the last week in the last 150 years. Berlin is also expecting a white winter, a rare occurrence in recent years, but even with a colder than normal start to December, demand has not risen enough to put pressure on gas prices. Thermostats are being turned up, but the de-industrialisation in Europe is more than enough to offset more demand for heating homes.

European gas inventories remain at a seasonal high, and while there’s been a rebound in Chinese imports, the country isn’t luring supply away from other regions – the worst-case scenario envisioned by analysts.

Thus Germany is much better prepared for the consequences of the end of Nord Stream gas. Previously entirely dependent on piped Russian gas with no LNG terminals on its coast at all, in the meantime it has hired several floating LNG (FLNG) terminals that allow imports, and is in the process of building at least one land-based terminal to diversify its energy supply options.

At the same time, the supplies of LNG from the US, which is emerging as the world’s leading supplier of the liquid form of the gas, have surged by a quarter in November compared to the same month last year, which means a steady flow of imports to Europe and a delay on big gas withdrawals from Europe’s tanks.

Nevertheless, this new energy system has little redundancy and remains vulnerable to shocks. If something goes wrong, like an accident or a broken terminal, then prices could soar. In the old system, Ukraine was transiting some 45 bcm of Russian gas to Europe a year, but the total capacity of the Ukrainian pipeline network is around 142 bcm, so there was massive redundancy built into the piped gas network. Sending extra gas to Europe from Russia via Ukraine is no longer an option. Indeed, Kyiv has sworn not to renew what is left of the Russian transit deal when it expires at the end of next year, removing more gas from what is left of the piped gas system.

The next important event is how much gas will be left in the tanks at the end of the heating season, which happens sometime at the end of March. In 2022, Europe ended the heating season with the tanks 25.5% on March 19 – well ahead of the technical 10% full acceptable minimum – and they were 29.9% full on March 25, the end of the heating season in that year.

Follow us online